During my study of Chinese Philosophy at Xiamen University I intensely engaged in Chinese Leadership Philosophy in order to find out if Chinese traditional Leadership Philosophy fits as cultural resource for Chinese Business Leadership.

In order to understand the base of Chinese Philosophy it might be worth to take a brief inside into Chinese history.

Summary of Chines history

The first written records dated back to the reign of King Wu Ding (1200-1180 B.C.) were Chinese characters written on turtle shells. The diviners recorded topics of the king’s interests and its possible outcomes and by applying heat the prediction could be deviated from the occurrent cracks on the shell. Due to the fact, that China still today uses the same writing system it is possible to read in this “ancient books” and study China`s more than 3000 years lasting history.[1] Another source used as early record of Chinese history are the bronze vessels built during the Shang dynasty, ca. 1766-1045 B.C. The differently shaped vessels, decorated with pattern, illustration of animals and inscriptions were used for cooking, storing food, drinking wine and performing rituals for ancestors.[2]

From these early written documents it is known, that the birth of female babies were less desired then the birth of a new male family member because sons are better in carrying on the family line than daughters; the Chinese distinguished staple food and accompanying cooked meat dishes; the Shang king ranked first in human society and was supported in ruling matters by several gods; in the hierarchy of the ancestors the long-dead outranked the more recently dead. The importance of the family line of nobles was kept within death, so the members of the same lineage were buried in one tomb. The hierarchy was kept alike and therefore the simultaneously killed “accompaniers-in-death” born out of noble families were buried close to their ruler, the corpse of the tomb guard near their weapons and as the most basic hierarchy level representatives the prisoners of war whose heads and limbs were separated from their body.[3]

It is further known that ritual sacrifices of animals, liquor and beer were extremely important for the relationship to various nature deities and to Shang Di who was regarded as the “first ancestor” of the people of Shang. However the people had sheep and cattle, the economy was based on agriculture. Tools they used were made of wood and stone – cheaper than the precious metal bronze which was mainly used at the king’s court; jade was already considered as precious good and a primitive kind of money was also introduced.[4] Therefore these early writings are evidence for the early Chinese Culture – the complex system of values, symbols, rituals and heroes.

When we talk about the history of China and her cultural development we have to consider, that China before her first unification in 221 B.C. as Zhong guo – middle empire or central state – consisted of different Chinese states, territories of several rivaling kingly families and their subordinates.[5]

Shang was followed by Zhou (1045-256 B.C.) – Western Zhou (1045-771 B.C.) and Eastern Zhou (770-256 B.C.) were paralleled by the Spring and Autumn Period (770-481 B.C.) followed by the Warring States Period (481-221 B.C.) which finally ended with the unification of China (221 B.C) under China’s first emperor Shi Huangdi, the reigning Qin King Zheng (259-210 B.C.).[6]

Since the Zhou dynasty the history provides important written documents for investigating the culture of the societies who later formed the Chinese culture. One of this literary evidence is “The Book of Changes” (Yijing) which consists of the notes of Zhou diviners in form of hexagrams. Since the notes are written in an “abstruse” language which needs a lot of interpretation, “The Book of Songs/Poetry” (Shijing) serves as an easier and better source for China’s ancient roots of culture. In contrast to the writings on the turtle shells, the bronze vessels or the writings of the Book of Changes, the Book of Songs represents information about the lives of the commoners. One of the latest songs within the book gives detailed information about the economic exchanges between lords and his dependents, depicts the pleasures, problems and activities of the people, who lived close to nature, extremely conscious of the changes in their natural environment.[7]

Another important contribution of the Zhou dynasty, which lasted almost 800 years, was the emergence of the great philosophical thinker who has influenced the Chinese culture in persisting and pervasive manner.

The period of Eastern Zhou was characterized by enormous changes within the realm of economy, politics and society which had evoked different kinds of philosophical activities. The early Chinese philosophers, first at all politicians who tried to find answers how to deal with the problems of society and politics, mainly reinterpreted classic writings – the Book of Songs, The Book of Changes, The Book of Documents, The Spring and Autumn Annals and the Book of Rituals – in order to draw their own teachings. This approach had been kept by Chinese scholars for over 2000 years and could be regarded as the the ancient foundation of China’s backward orientation.[8]

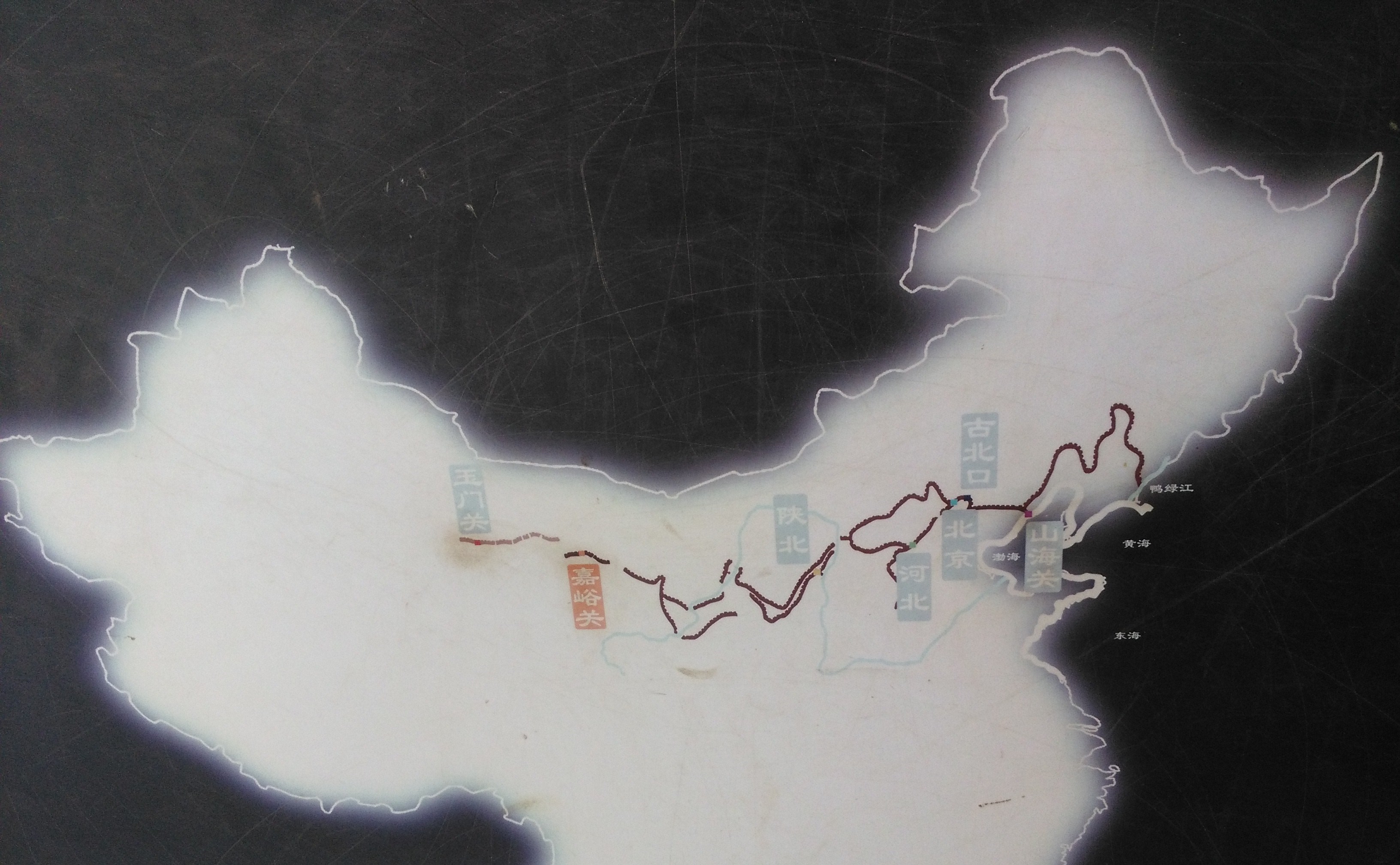

Not only could the backward orientation be seen as typical character of Chinese culture also the closeness, symbolized by the building of the Great Wall (started during the Qin dynasty)[9] in the North for protecting the central plains occupied by the agricultural Chinese from the nomadic “barbarians”[10], had contributed to China’s closed development.[11]

Inside the wall different ethnics and people with different beliefs could live in harmony, mostly after small or sometimes large conflicts between the different groups were ended by integration of the alien culture into the Chinese culture. Therefore the Chinese culture was permanently challenged by accepting “new” foreign and getting rid of “old” cultures. We can recognize three “open” periods, in which “barbarian” cultures were integrated into the Chinese culture.

The first of this open periods could recognized during the Eastern Zhou (770-221 B.C.), the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period, just before China had been firstly unified in 221 B.C..[12] Short after the death of the first Emperor in 210 B.C. the Han dynasty was established in 207 B.C. and lasted after a brief usurpation until 220 A.D..[13] The Han dynasty is still today recognized as a very flourishing and well developed period within China’s history (mentioned in one step with the Roman Empire) and was very influential toward the development of China’s culture.

Confucianism became the official ideology theory and the classical writings[14] were selected to pay special attention as scholarly books for scholar’s education. This act could be recognized as the “first step in the formation of the Confucian canon”[15]. Furthermore the first “professional” history book about China’s history and therefore records of Chinese culture – the “Records of the Grand Historian” – was written by the Chinese historian Sima Qian (145- ca. 90 B.C.), a great son of the Han people who is recognized as the “father of Chinese historiography” [16]. Also an important fact regarding the development of Chinese culture is the fact, that the vast majority of today’s China’s people are descendants of “men of Han”.[17]

The second period of important and wide cultural and ethnical integration happened during the time of Wei Jin Northern and Southern Dynasties between 220 and 589 which is also known as “The Six Dynasties Period”[18] or “Period of Division”. In comparison with the first period of cultural integration, the second period had taken place within a larger territory – the Central Plain culture, the minority culture in the northwest of China and the Buddhist culture – and included a wider range of ethnics.[19] The importance of Confucian thoughts and teachings was diminished, the Daoist thinking “rose prominently to the surface of Chinese society” – especially among the common people and last but not least, the Buddhist culture influenced the Chinese spirit.[20]

In order to represent the crucial situation of that time, Fairbank and Reischauer cite a hopeless observer of the 4th century history who feared that the days of the Chinese Empire were over. “North China, the heartland of the empire, was completely overrun by “barbarians”; South China was obviously incapable or restoring imperial unity; and the whole land was being swept by a foreign religion which had an otherworldly emphasis and a celibate, monastic ideal that cut at the roots of Chinese philosophy and the family-centered social system”.[21]

Alike the first period of cultural integration was followed by the highly flourishing Han dynasty, the second period ended in the founding of Tang Dynasty which is recognized as the “golden age” of China. Tang ruled an enormous territory (from southern Siberia to Southeast Asia and westward through Tibet and Central Asia to the Caspian Sea)[22], great poets and artist lived during this glorious time and the government had improved its efficiency.[23]

Whereas in the first “open” periods cultures of South and North China (first period), and the Central Plains culture with minority groups of the Northwest and Buddhism (second period) were blended, the third period has started with blending ideologies and cultures from East and West. Started with the first Opium War in 1840 Western culture was integrated within three stages – introducing artifacts (weapons, equipment and the Northern Fleet), introducing institutions (new system of constitutional monarchy) and introducing ideologies (which is still in process today). By these large scale impact completely new doctrines, theories and development like the theory of evolution, the idea of democracy and modern science were introduced into the long lasting culture of China what caused confusion and changes to Chinese thoughts.[24] Therefore the Opium War is regarded as the turning point in Chinese history.[25]

Followed by the “Treaty of Nanjing” (signed in August 1842) the influence of Western Cultures increased, mainly stimulated by the foreign settlements within the new treaty ports like Shanghai. The later signed treaties in 1856-60 caused growing immigration of Christian missionaries which led to establishment of hospitals, churches and schools for the Chinese population.[26]

The ongoing western stimulated modernization, which caused a split within the Chinese society, remained mainly restricted to the cities of the new treaty ports and could not spread into the broad stream of Chinese tradition because traditional scholars moved from the inland provinces to the sea frontier into official life and not the other way.[27]

After some domestic revolts and rebellion (most known and aggressive: Taiping Rebellion 1860-62), the Qing government who was quite ambiguous toward the development within the modern “treaty-port East” and had already lost control over the vital elements of the country, tried to “self-strengthen” China by the idea to “learn the superior technology of the barbarians in order to control them” and simultaneously “restore the old Confucian system”. The model of “change within tradition”-restoration was characterized by static harmony, limited to the ancient Confucian model.[28]

This resulted in the new doctrine: “Chinese learning for the essential principles, Western learning for practical application”.[29]

One model in person of this “hybrid culture” was Sun Yat-sen. Born into a poor, traditional rural farmer household he went to foreign countries in order to gain the knowledge and find allied revolutionaries to influence China’s fade.[30]

After returning from his “study trips” in the United States, Europe and Japan, Sun combined his multicultural knowledge within a doctrine to organize and guide a republican revolution. With his concept of “Three Principles of the People” (nationalism, democracy and people’s livelihood) he accepted the abolishment of the Confucian hierarchy by the implementation of the egalitarian principle of democracy.[31]

In 1911 the long tradition of dynastic reign was vanished, Qing lost its “Mandate of Heaven” and almost all Chinese provinces had declared their independence. This Revolution who led to the founding of “Republic of China” was supported by “Overseas Chinese funds, secret society contacts, new student leadership, the revolutionary ideology” and finally by Japan’s encouragement.[32]

During the following years through the popular search for new identity the strength and complexity of Chinese Nationalism was steadily growing.[33]

With their “New Cultural Movement” (starting with the May 4th incident in 1919) the new intellectuals (students, professors, writers and journalists) attacked the old Confucian order of hierarchy and status in order to liberalize the individual (subject from ruler, son from father, wife from husband); and evoked increasing opposition of the advocates of Chinese antiquity.[34]

Sun Yat sen who was searching for potential power to reorganize his nationalist party Kuomingtang recruited students from the modern intellectual movement. The missing political program for the domestic revolution of the Nationalist power was provided by Russia (in form of a Communist-led proletarian revolution of industrialized Europe) because it fits the needs of the party’s revolutionary program best to reunify the nation (which was under control of different warlords) and stop foreign imperialism. However the Nationalist Revolution was successful within the western influenced cities mainly at the east coast failed at the countryside characterized by ancient traditions.[35]

After the Nationalist Revolution ended with limited results, China’s nation was caught within an ongoing fight at the domestic frontline between the Communists and Nationalist as also within the war against the invading Japanese. Demanded by the Western powers, the two competitive parties had formed an alliance against Japan in the beginning but finally clashed with each other and ended in the Civil War. Finally in 1949 on the 1st of October, after almost three decades of hard struggle, Mao Zedong proclaimed the new “People’s Republic of China”.

The years of War and destruction were followed by reconstruction and restructure in order to re-establish political, economical, military and social order in China. For this the new established central government under the lead of Mao Zedong, had enforced several mass campaigns directed against inefficiencies and corruption, religious sects, secret-societies, labor-racketeering organizations and finally against the bourgeoisie of urban China. In their ambitious attempts to ensure law and order and to reorganize China’s stricken society the party leadership helped themselves with highly pragmatic approach.[36]

Campaigns like “the Hundred Flowers campaign” were officially enforced to reveal hidden rightists in the country but primarily evoked to bring conflicting attitudes within the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) leadership to the surface. Out of the conflicts about the mode of development, the “Great Leap Forward” sprang up, officially to improve people’s living standard and to accelerate economic growth. Fantastic dreams what had finally ended in disaster for millions of people.[37]

Finally in 1960[38] with the break of the “brotherly” relationship to Communist Russia, the doors of China for and to the outside world had been closed in order to create a new and purified society.

With the launch of the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” in 1966 Mao and his leaders called for attacking the “four old” societal elements: old customs, old habits, old culture and old thinking. After spreading the revolutionary sprit within factories, communes, schools and work units and organizing local “Red Guards” enthusiastic students were activated to prove their revolutionary integrity through violent campaigns. After ancient buildings, temples and art objects were demolished or destroyed, teachers, schools administrators, party leaders and parents were cruelly attacked respectively murdered the entirely population did not know what to believe.[39] The values of the Chinese society rooted within China’s ancient culture were deeply shaken.

In 1973 several years after the official end of the Cultural Revolution, the erasement of Confucian thoughts still were continued by burning Confucian books and burying Confucian scholars alive. This “Anti-Lin Biao anti-Confucius” movement were again initiated out of internal disagreements within the Chinese leadership in combination with massive problems to re-establish China’s educational system which was almost completely destroyed through the destructive power of the previous revolutionary campaign.[40]

After Deng Xiaoping has reopened China for and to the outside world in 1978 he encouraged China’s people to engage in private business and therefore materialism became the leading power for the majority. People without education, motivated with their own business idea, emerged to the new backbone of modern pragmatic China. Deng Xiaoping’s statement “No matter if it’s a white cat or a clack cat, it is a good cat if it catches mice”[41], pragmatism had become the new leading thought in order to pursue individual wealth. At this time also the modern sciences were much more important within the educational system than traditional Chinese education in the philosophical classics therefore the ancient Chinese culture seemed to be uprooted. Since the ancient time, business people as part of society had been treaded without any respect and business stagnated for more than two thousand years and suddenly by the new reform highly appreciated as the new nation’s power what had caused substantial confusion.[42]

The late 1990s signed a turning point of the “downhill”[43] trend within the traditional value system of China’s society by revitalizing the traditional national culture. This “Guoxue tide” (learning of traditional Chinese culture), initiated to help China to realize “modernization” peaked by launching the “Harmonious Society” social movement in 2005 by President Hu Jintao. Lectures, forums and seminars were initiated and also primary schools had started to teach the Chinese philosophical classics. After Confucianism was rehabilitated finally in 2007, the 21st century could be regarded as the survival period of the ancient major ideology in China.[44]

[1] Hansen (2000), p. 17; 19; [2] Hansen (2000), p. 30, 17; Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 27; [3] Hansen (2000), p. 26; 31-34; [4] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 28; [5] Hansen (2000), p. 97; [6] Hansen (2000), p. 103; [7] Hansen (2000), p. 43-44; [8] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 40-42; Shi, Chen (2008), p. 12; [9] Hansen (2000), p. 104; [10] Fairbank, Reischauer, (1978), 57; [11] Shi, Chen (2008), p. 7; [12] Shi, Chen (2008), p. 13; [13] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 59; [14] mentioned within the previous paragraph: The Book of Songs, The Book of Changes, The Book of Documents, The Spring and Autumn Annals and The Book of Rituals; [15] Hansen (2000), p. 127; [16] Hansen (2000), p. 35; [17] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 60; [18] Fairbank, Reischauer. (1978), p. 83; [19] Shi, Chen (2008), p. 14; [20] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 84; Shi, Chen (2008), p. 14; [21] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 93; [22] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 98; [23] Hansen (2000), p. 196; [24] Shi, Chen (2008), p. 15-16; 31; [25] Fu et al (2007), p. 880; [26] Spence (1990), p. 161; [27] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 285, 340; [28] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 309, 312, 317; [29] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 372; [30] Spence (1990), p. 227; [31] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 410-411; [32] Fairbank, Reischauer. (1978), p. 411, 413; [33] Spence (1990), p. 238; [34] Fairbank, Reischauer. (1978), p. 435-436; [35] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 439ff; [36] Spence (1990), p. 437ff; [37] Spence (1990), p. 574; [38] Spence (1990), p. 440; [39] Spence (1990), p. 440, 606; [40] Spence (1990), p. 636; [41] Wang, Chee (2011), p. 23; [42] Wang, Chee (2011), p. 18-19; [43] Wang, Chee (2011), p. 19; [44] Tang (2015), p. 4; Wang, Chee (2011), p. 19

Philosophical „DNA“ of Chinese Culture

With the “conforming to the rhythm of the Universe”[1] the natural state of Harmony in the Universe built the underlying wisdom of all Chinese thinking. In this, the Universe as an organic system integrates Heaven, Earth and what exists in between into a well-ordered whole. In this holistic concept, “Heaven” symbolizes the “totality of heavenly bodies and phenomena” [2] and “Earth” is regarded as a synonym for the ground on which everything exists. The “men” what is synonymously used for all human beings, symbolize all what is exiting between Heaven and Earth. By an existing spiritual correspondence natural disasters are evoked by men through some unfavorable affairs as a form of natural development. Consequently a kind of evil force in the Universe does not exist within the Chinese thinking and therefore all what happens is part of the naturally organized Universe.[3]

The philosophical thoughts of the “Yijing” (易经) or “The Book of Changes”, which is honored as the “mother” of Chinese Philosophy, emphasizes the constitutional duality of “Yin” (阴) and “Yang” (阳) which is causal for all that happens in Heaven and Earth. The two antithetic and complementary forces are held in a state of “continual transition” through which a permanent change is taking place within the substantial world. So the Chinese Philosophy is based on a Cosmology of permanent change, caused by the alternation of Yin and Yang.[4]

The early Chinese philosophers, who emerged during the “Spring and Autumn” period (722-476 B.C.) and “Warring States” period (475-221 B.C.) of the Zhou Dynasty (1122-221 B.C.) were first of all politicians within an era of permanent fights and social unrest. They mainly reinterpreted the Classic writings like “The Book of Changes” (易经yi jing), “The Book of Songs” (诗经shi jing), “The Book of Documents” (书经shu jing), “The Spring and Autumn Annals” (春秋chun qiu) and “The Book of Rituals” (礼经li jing or li ji), in order to find answers about “how to deal with the contemporary problems of society and politics”. This approach had been kept by Chinese scholars for over 2000 years and could be regarded as the foundation of “China’s backward orientation”.[5]

During this period of enormous disorder “Hundred Schools of Learning”[6] with sometimes contrary believes and thoughts emerged and have been continuously build the inclusive “DNA” of Chinese Culture.[7] The inclusiveness refers to the Chinese tolerant “dou keyi” (都可以both, or all “ok”) attitude towards a variety of different and also conflicting ideologies.[8]

Based on the above described cosmology, the Schools of Confucianism, Militarism, Legalism and Daoism are focused on human society and have tried to find answers about how to rule a state effectively in order to reestablish the natural state of Harmony.

School of Confucianism

Although Confucius (孔子 kong zi 551-479 B.C.) is regarded as the founder of the Confucian School and the Analects of Confucius as the key text for his thoughts, Confucianism is far more than the book about the ideas and discussions between “Master Kong” and his students which were focused on the ancient thoughts of the Sage Kings. During the glorious Han Dynasty (207 B.C.-229 A.D.), Confucianism first had become the official ideology and the “Five Classics”[9] – as already mentioned previously – were selected for the scholar’s education. By adding the “Four Books”, namely “The Great Learning” (大学da xue), “The Doctrine of the Mean” (中庸zhong yong), “Mencius” (孟子meng zi) and “The Analects” (论语lun yu) the collection of Confucianism was completed. The Analects of Confucius, composed by his students and disciples, were used to teach the Confucian morality and appropriate behavior in order to create harmony for a good life.[10] Therefore the book can be regarded as reliable source to study the value orientation of Chinese Culture.

In the Confucian Philosophy a person’s identity, the person’s SELF, is determined by its relationship to others through the conviction, that an individual is a bearer of role responsibilities instead of having individual rights. All human beings are vital elements of the entire Universe and play an important role in establishing a harmonious society.[11]

Social harmony is established, when every person is following its obligations and responsibilities, assigned to one’s role as noted in the Analects: “Let the ruler be ruler, ministers ministers, fathers fathers, sons sons.”[12] Loyalty is required “toward the role one plays” and can be understood as “doing what one is supposed to do”; therefore someone’s “social role is not simply a social assignment; it is also a moral assignment”[13]. The moral obligations are fixed and following the Confucian model of the strongly hierarchical order of superiority and inferiority. The whole society has to be organized according to the Confucian model of relationships between sovereign and minister, father and son, husband and wife, elder brother and younger brother, and friend and friend in order to establish harmony.[14]

Through the given hierarchical structure the proper rectification of names should establish a peaceful society. The name of a specific role determines rules of conduct appropriate to each social relation.[15] By rectifying and maintaining names, the reality is categorized in various levels in order to balance demands and responsibilities within the society. The “Golden Rule”: “What I do not wish others to do to me, I do not wish to do to others,”[16] is regarded as the moral guiding principle. By the herein taught empathy “one can also extend oneself to appreciate what the other person in the opposite role would desire,”[17] and keeps the way of humanity.

The basic assumption for cultivating the way of humanity successfully is the inborn good nature of all humans. According to Mencius all humans possess a good nature that is given by the Nature: “Man’s nature is naturally good just as water naturally flows downward. There is no man without this good nature; neither is there water that does not flow downward.” and: “If you let people follow their feelings (original nature), they will be able to do good. This is what is meant by saying then human nature is good.”[18]

But according to Confucius having a good nature is not enough in order to be a good person. So each individual has to be cultivated in order to become virtuous, noted in the Analects book XVII chapter 2: “by nature close to one another, through practice far distant”[19] and further described in book VII chapter 3: “That I have not cultivated virtue, that I have learned but not explained, that I have heard what is right but failed to align with it, that what is not good in me I have been unable to change – these are my worries.”[20]

Since being virtuous is not an inborn attitude Confucius has emphasized the need for continuous learning and reflecting on one’s own. Therefore the advice given in the Analects book I chapter 1 stresses the importance of Self-cultivation by learning and reflection: “To study and at due times practice what one has studied, is this not a pleasure? (…).”[21] By its mention right in the beginning of the Analects, the School of Confucianism stresses the importance of the concept of Self-cultivation in order to develop a virtuous character.

With the two fundamental, mutually dependent concepts of “ren” (仁) as humanity and “li” (礼) as behavioral propriety Confucius explains his ideal of cultivated humanism[22] in which ren serves as initial element of humanity: “only the ren person can love others and hate others”[23] and builds therefore the essence of “the Golden Rule” in terms of conscientiousness and altruism.[24] According to his philosophy recorded in book VII chapter 30 of the Analects: “The Master said, Is ren distant? When I wish to be ren, ren arrives”[25], everybody has the ability and possibility to become “ren”.

Without being ren it makes no sense to learn behavioral propriety li: “the Master said: If a man is not ren, what can he do with li? (…).”[26] In the Confucian Philosophy “li” can be understood as the concept which “helps to mark each person’s place within networks of relationships”[27]. By determining the right behavior according to a person’s social position within different kinds of situations, li is instrumental in realization social harmony: “Master You said: In the practice of li, harmony is the key. (…) To act in harmony simply because one understands what is harmonious, but not to regulate one’s conduct according to li: indeed, one cannot act in that way.”[28]

The basic concern of the Confucian educational, moral and political program, applicable for every element of the society, is the cultivation of humanity “ren” and behavioral propriety “li”: “The Master said, there is a teaching; there are no divisions.”[29] For the teaching of the “dao” (道) as the Way of virtue which defines the right way Confucius’ own development should be taken as model: “When I was fifteen I set my heart on learning. At thirty I took my stand. At forty I was without confusion. At fifty I knew the command of Tian [Heaven]. At sixty I heard it with a compliant ear. At seventy I follow the desires of my heart and do not overstep the bounds.”[30]

By summarizing the idea of Confucius, the purpose of self-cultivation is the development of cultivated men, as virtuous elements of the society, who are able to do the right things and also do the things right without thinking about it. Thus the main concern is to develop a kind of “moral auto pilot”, which makes law and punishment within a harmonious society unnecessary.

Sunzi’s Art of War and his school of Militarism

The philosophy of Sunzi (孙子ca. 544-496 BC) recorded in the “Art of War”, provides a comprehensive concept about how a state can be governed successfully, especially in times of war: „art of war is of vital importance to the state”[31]. Although Sunzi’s concept provides a guideline for military tactics through methods and discipline in order to operate the war successfully, his most important concern is how to avoid fighting: “(…) supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’ resistance without fighting.”[32] But if fighting is unavoidable, the Leader of an army should consider about “The five heads”[33] as crucial factors of success:

- The Moral Law causes the people to be in complete accord with their ruler, so that they will follow him regardless of their lives, undismayed by any danger

- Heaven signifies night and day, cold and heat, times and seasons

- Earth compromises distances, great and small; danger and security; open ground and narrow passes; the chances of life and death

- The Commander stands for virtues of wisdom, sincerity, benevolence, courage and strictness

- Method and discipline are to be understood the marshaling of the army in its proper subdivisions, the graduations of rank among the officers, the maintenance of roads by which supplies may reach the army and the control of military expenditure

“These five heads should be familiar to every general: he who knows them will be victorious; he who knows them not will fail.”[34] “Hence the saying: If you know the enemy and know yourself, your victory will not stand in doubt; if you know Heaven and know Earth, you may make your victory complete.”[35]

In his philosophical thoughts Sunzi has applied the Confucian Philosophy as Moral Law as one of his five factors of success. He furthermore emphasized on the natural way of Harmony and therefore the alternation of natural forces given by Heaven and Earth. One of the most outstanding features of Sunzi’s Philosophy is the detailed description of several tactical and operational advices which has influenced the Chinese implicit leadership theory especially in giving the leading responsible the necessary authority and operational power.

The Legal School of Hanfeizi

Hanfeizi (韩非子280-233 B.C.) who was initially a student of Confucius disciple Xunzi (荀子), whose thoughts are regarded as the beginning of the legalist thinking in China’s Philosophy, became a strict opponent of the Confucian political Philosophy and is commonly regarded as the “synthesizer of Legalism”. As political advisor, he became one of the most prolific philosophers in ancient China and has mainly influenced the Qin emperor’s policy which has contributed to China’s first unification in 221 BC after the Warring State Period.[36]

Although Hanfeizi’s teacher Xunzi advocated the “bad nature” of humans, Hanfeizi himself was not really interested in the definition of human nature. Guided by his claim that humans are naturally seeking to benefit themselves, he was more interested in developing a concept to control human behavior. Therefore he has changed the importance of self-cultivation into the necessity of strict regulation by law and bureaucracy. Hanfeizi’s Legalist Philosophy rejects the importance of relationship in each aspect of life, especially in the public and professional life and shows herein a clear opposition to the Confucian Philosophy.[37]

Whereas the Confucian thinkers believe that morality and politics are mutually interwoven and the perfected Leader leads his followers by serving as role model for the right behavior, the Legalists in general separate politics from morality. Hanfeizi claimed that in a more and more complicated world the pattern of ancient models could not provide an adequate concept for govern and ruling a complex state.[38]

Laozi’s Philosophy of the Dao

In contrast to the human orientation of the Confucian, Military and Legalist Philosophy who are emphasized on the importance of culture and civilization through cultivation, the Daoist Philosophy, founded by Laozi (老子ca. in the 6th century B.C.), put the highest emphasize on the natural “Dao” (道way).

In his idea the eternal way “Dao” could not be named, has no fixed beginning and because it could not be exhausted, it has no end. The “Dao” is regarded as the womb of all material and non-material things and is therefore recognized as the ultimate beginning of ALL.

Recorded within chapter 1 of the “Dao de jing” (道德经) or alternatively called “The Laozi” (老子): “The Tao (Way) that can be told of is not the eternal Tao; The name that can be named is not the eternal name. The Nameless is the origin of Heaven and Earth; The Named is the mother of all things. (…)”.[39] Furthermore as written in chapter 42: “Tao produced the One. The One produced the two. The two produced the three. And the three produced the ten thousand things. The ten thousand things carry the yin and embrace the yang, and through the blending of the material force (chi) they achieve harmony. (…)”[40]. In chapter 4 Laozi explains that “Tao is empty (like a bowl), It may be used but its capacity is never exhausted. It is bottomless, perhaps the ancestor of all things. It blunts its sharpness, It unties its tangles. It softens its light. It becomes one with the dusty world. Deep and still, it appears to exist forever. I do not know whose son it is. It seems to have existed before the Lord.”[41]

Because everything comes from and follows the natural Dao humans in Laozi’s idealistic plan do not need a concept of morality because they are good by nature. All are living within a harmonious and natural world which makes “man made” intervention almost unnecessary.[42] He explains in chapter 18: “When the great Tao declined, The doctrines of humanity (jen) [ren] and righteousness (li) arose. When knowledge and wisdom appeared, There emerged great hypocrisy. When the six family relationships are not in harmony, There will be the advocacy of filial piety and deep love to children. When a country is in disorder, There will praise of loyal ministers.”[43] By this statement within his “Dao De Jing” it becomes obviously that Laozi clearly criticizes the Confucian philosophy and consequently stresses the good characteristics of human nature which makes civilization through cultivation unnecessary.

By suggesting: “Abandon learning and there will be no sorrow”[44], Laozi advocates a concept of “negative self-cultivation” and therein Laozi’s philosophy shows a crass opposition to the Confucian concept of self-cultivation. In order to tread the right way so Laozi in chapter 48: “The pursuit of learning is to increase day by day. The pursuit of Tao is to decrease day after day. It is to decrease and further decrease until one reaches the point of taking no action.”[45] What means, for becoming a virtues man, self-cultivation is unnecessary, because the following of the Dao leads naturally to the ultimate wisdom.

The eternal Dao is “the way things should be”[46]and “the all-embracing quality of the great virtue (te) follows alone from the Tao. (…).”[47] Change and alternation, the main components of the already introduced cosmology of permanent change, is one of the basic elements of the Daoist Philosophy: “Reversion is the action of Tao.”[48] By the natural alternation of Yin and Yang things will be done in a natural way without human’s interfere: “When the people of the world all know beauty as beauty, There arises the recognition of ugliness. When they all know the good as good, There arises the recognition of evil. Therefore: Being and non-being produce each other; Difficult and easy complete each other; Long and short contrast each other; High and low distinguish each other; Sound and voice harmonize with each other; Front and back follow each other. Therefore the sage manages affairs without action (wu-wei)(…).”[49] “Wu-wei 无为” what is literary translated with “non-action” and means “taking no action that is contrary to Nature”[50] describes the Daoist wisdom

Through the perception that the Daoist virtue is immortal, because: “(…) He who does not lose his place (with Tao) will endure. He who dies but does not really perish enjoys long life”[51] the philosophy of the “Dao De Jing” has introduced the idea of immortality to the Chinese Philosophy.

With its Dao-centered ideal Laozi’s philosophy emphasizes the importance of simplicity, spontaneity, tranquility, weakness and non-action in order to walk the natural way of life – follow the Dao and be in Harmony with the Nature, Laozi has influenced the “Chinese mind just as much as Confucianism does”[52].

The scholars Fu et al, operating the specific investigation for the Chinese Culture of the GLOBE study, have emphasized that although the thoughts of the Daoist School are regarded as the other major philosophy, it is Confucianism that has continuously influenced the Chinese people and formed the Chinese culture. So Confucianism is almost used as synonym for describing the “Chinese traditional culture”[53] and the Analects of Confucius, which are mainly discussing human values, can be regarded as the source book for the unique Chinese value orientation.

[1] Kaltenmark (1965), p. 46; [2] Liu (2006), p. 2; [3] Liu (2006), p. 2; [4] Liu (2006), p. 26-28; [5] Fairbank, Reischauer (1978), p. 40-42; Shi, Chen (2008), p. 12; [6] Lai (2008), p. 3; [7] Shi, Chen (2010), p. 9; Wang (2011), p. 9; [8] Shi, Chen (2008), p. 24; [9] The Book of Changes, the Book of Songs The Book of Documents, The Spring and Autumn Annals and the Book of Rituals; [10] Chen, Lee (2008), p. 32; Liu (2006), p. 48; [11] Ihara (2004), p. 12; 23; [12] The Analects book XII chapter 11 in Eno (2015), p. 62; [13] Liu (2006), p. 50; [14] Liu (2006), p. 49; [15] Liu (2006), p. 51; [16] The Analects book V chapter 12 in Eno (2015), p. 20; [17] Liu (2006), p. 55; [18] Mencius 6A:2, 6A:5 in Chan (1963), p. 52; 54; 51; [19] The Analects book XVII chapter 2 in Eno (2015), p. 94, [20] The Analects book VII chapter 3 in Eno (2015), p. 30; [21] The Analects book I chapter 1 in Eno (2015), p. 1; [22] Lai (2008), p. 19-21; [23] The Analects book IV chapter 3 in Eno (2015), p. 14; [24] Chan (1963), p. 16; [25] The Analects book VII chapter 30 in Eno (2015), p. 34; [26] The Analects book III chapter 3 in Eno (2015), p. 9; [27] Lai (2008), p. 42; [28] The Analects book I chapter 12 in Eno (2015), p. 3; [29] The Analects book XV chapter 39 in Eno (2015), p. 87, [30] The Analects book II chapter 4 in Eno (2015), p. 5; [31] Sunzi book I chapter 1 in Giles (1910), p. 1; [32] Sunzi book III chapter 2 in Giles (1910), p. 9; [33] Sunzi book I chapter 3-10 in Giles (1910), p. 1; [34] Sunzi book I chapter 11 in Giles (1910), p. 1; [35] Sunzi book X chapter 31 in Giles (1910), p. 49; [36] Liu (2006), p. 182; [37] Lai (2008), p. 172-175; [38] Liu (2006), p. 189; [39] Laozi chapter 1 in Chan (1963), p. 139; [40] Laozi chapter 42 in Chan (1963), p. 160; [41] Laozi chapter 4 in Chan (1963), p. 141; [42] Liu (2006), p. 145; [43] Laozi chapter 18 in Chan (1963), p. 148; [44] Laozi chapter 20 in Chan (1963), p. 159; [45] Laozi chapter 48 in Chan (1963), p. 162, [46] Liu (2006), p. 143; [47] Laozi chapter 21 in Chan (1963), p. 150; [48] Laozi chapter 40 in Chan (1963), p. 160; [49] Laozi chapter 2 in Chan (1963), p. 140; [50] Chan (1963), p. 136; [51] Laozi chapter 33 in Chan (1963), p. 156; [52] Liu (2006), p. 150; [53] Fu et al. (2007), p. 878

Chinese traditional Leadership Philosophy as cultural resource for modern Chinese Business Leadership

The main findings of my masterthesis are summarized within the short presentation:

Diese Diashow benötigt JavaScript.

Please feel free to contact me for more detailed information and some discussions.

Chinese traditional Leadership Philosophy

Within the follow paragraph you may find some helpful perspectives and ideas for your leadership role. The inputs are part of my master thesis about Chinese traditional Leadership Philosophy

Confucian concept of Moral Leadership

The following presentation shows that the main purpose of Confucian Leadership is to cultivate harmony within the state through establishing a moral society in which each individual fulfils its moral obligation according to its defined position.

When the state is in a harmonious balance people will be attracted from outside and have no interest to be involved in politics: “(…) Those nearby are pleased, those far distant come.”[1] As already introduced within chapter 3.1, everybody within the Confucian society has an assigned role with associated obligation and so popular interest in government is a sign of political failure. An interfere of the people would only become necessary in case the leader has lost his “mandate of heaven” caused by his failure to tread the way of virtue.

So the Confucian ideal is to govern by moral authority in which authority is earned by virtue which implicitly includes the parental care for the obedient followers. Since the legitimacy for a leader is derived from his moral character which is not given by nature, morality and wisdom has to be developed through the lifelong process of self-cultivation. With his consequently moral perfected character, the virtuous leader serves as teacher for the people in order to develop individual morality which contributes for a moral society. Therefore the morally perfected man is the most important element of the Confucian harmonious society and according to James Legge occupies the central position within the Confucian concept of Leadership.[2] This is evident by the notion within the Analects: “when one rules by means of virtue it is like the North Star – it dwells in its place and the other stars pay reverence to it.”[3]

Junzi, the Moral Leader with a benevolent heart

In the Analects we can find the Confucian concept of a virtues man. He is one who “bring broad benefits to the people and be able to aid the multitudes (…) is one who, wishing himself to be settled in position, sets up others; wishing himself to have access to the powerful, achieves access for others. To be able to proceed by analogy from what lies nearest by, that may be termed the formula for ren.”[4]

The “Junzi”, 君子literally translated with gentleman, is a man of high virtue who does not only show his perfected characteristics in fulfilling his professional role of a leader: “if one takes ren away from a junzi, wherein is he worthy of the name? (…)”[5]

To be a Confucian Junzi means carrying the virtue of “ren” during all his life, in each situation: “(…) There is no interval so short that the junzi deviates from ren. Though rushing full tilt, it is there; though head over heels, it is there.”[6] He is a man of perfected wisdom who takes it as his moral responsibility to create a culture of morality. His moral responsibility is not restricted to his professional position within the organization: “he can find himself in no situation in which he is not at ease with himself” and so the “superior man lives peacefully and at ease and waits for his destiny”.[7] In case that the talents of the perfected man remain unrecognized he has no reason to be angry about: “(…) To remain unsoured when his talents are unrecognized, is this not a Junzi?”[8]

A good leader has to be first of all a man of humanity and therefore “ren” is the basic requirement within the Confucian concept of Leadership. “A junzi who is not ren, there are such people. There has never been a small man who is ren.”[9] For a good leader nothing is more important than humanity: “Ren is of greater moment to the people than water or fire. I have seen people tread through water and fire and died; I have yet to see anyone tread through ren and die.”[10]

Although the Confucian Junzi is a man of strict authority he has a benevolent heart: “Ji Kangzi asked (…), How would it be if I were to kill those who are without the dao in order to hasten others towards the dao? Confucius replied, Of what use is killing in your governance? If you desire goodness, the people will be good. The virtue of the Junzi is like the wind and the virtue of common people is like the grasses: when the wind blows over the grasses, they will surely bend.”[11] Also in situations outside of his department of responsibility or outside the organization, a Confucian leader treats the people with humanity and benevolence and acts according the Way of virtue: “When you go out your front gate, continue treat each person as though receiving an honored guest. When directing the actions of subordinates, do so as though officiating at a great ritual sacrifice. Do not do to others what you would not wish done to you. Then there can be no complaint against you, in your state or in your household.”[12]

As already presented within the introduction of the traditional Philosophy in chapter 3.1, the good nature of each human element of the society is not enough to follow the way of virtue. In order to become a legitimated leader, a man has to cultivate a virtuous “self” by following the Confucian concept of “self-cultivation”: “The Master said, The gentleman who is resolute and ren does not seek to live on at the expense of ren, and there are times when he will sacrifice his life to complete ren.”[13]

Becoming a Junzi through Self-cultivation

Whereas self-cultivaton is everybody’s duty in order to tread the path of virtue: “From the Son of Heaven down to the common people, all must regard cultivation of the personal life as the root or foundation.”[14], for becoming a real Junzi a man has to do his utmost to reach the highest: “the Junzi gets through to what is exalted; the small man gets through to what is base.”[15] Only those who are able to gain perfected virtue are able to lead others in order to establish harmony: “The superior man tries at all times to do his utmost in renovating himself and others”[16].

The main duty of a virtuous man is to achieve a high grade in self-cultivation in order to perfect his “dao” and become a man of wisdom: “Artisans of all types dwell in their workshops to master their crafts; the Junzi studies to perfect his dao.”[17] In his ambition to do his utmost a virtuous character distinguishes the leader from the followers: “By nature close to one another, through practice far distant.”[18]

Not only Confucius and Mencius, but also their controversial combatant Xunzi stresses the importance of self-cultivation in order to develop a good character and perfected virtue for getting the heavenly legitimation to lead the people. The responsibility for becoming a man of perfected wisdom depends on the person’s ability, motivation and will to cultivate one’s self as recorded by Xunzi: “As to cultivating one’s will, to be earnest in one’s moral conduct, to be clear in one’s knowledge and deliberations, to live in this age but to set his mind on the ancients (as models), that depends on the person himself. Therefore the superior man is serious about what lies in himself and does not desire what comes from Heaven. The inferior man neglects what is in himself and desires what comes from Heaven. Because the superior man is serious about what is in himself and does not desire what comes from Heaven, he progresses every day. (…) The reason why the superior man progresses daily and the inferior man retrogresses daily is the same. Here lies the reason for the great difference between the superior man and the inferior man (…).”[19]

A man who wants to become an effective leader firstly has to cultivate his self and so the duty of successful self-cultivation could be regarded as the basic requirement to develop effective leadership, recorded within the Analects: “The Master said: if one can make his person upright, then what difficulty will he have in taking part in governance? If he cannot make his person upright, how can be make others upright?”[20] If he is successful in self-cultivation, he would be able to teach his followers in order to help them to cultivate their morality and become an accepted leader.

Self-Cultivation through learning and reflection

The Junzi as a superior person who has a moral exemplary character has to cultivate his self by learning and reflecting. Both are mutual important components of self-cultivation – one without the other is less valuable in cultivating a moral character: “if you study but don’t reflect you’ll be lost. If you reflect but don’t study you’ll get into trouble”[21].

For a successful learning, the wisdom of the “great men”, recorded in the Classic Books[22], should be taken as reliable resource: “The Junzi holds three things in awe. He holds the decree of Tian [Heaven] in awe, he holds great men in awe, and he holds the words of the Sage in awe. (…)”[23]

For a successful reflection three questions one has to ask oneself: “(…) In planning for others, have I been loyal? In company with friends, have I been trustworthy? And have I practiced what has been passed on to me?”[24] But before one can reflect on these questions, the already learnt has to be put in practice: “The Master said: To study and at due times practice what one has studied, is this not a pleasure? (…)”[25] So, right in the beginning of the Analects the importance of learning and the application of the learned is emphasized and introduced as a life-long pleasure.

For a successful self-reflection one has to be sincere: “Sincerity means the completion of the self, and the Way is self-directing. Sincerity is the beginning and end of things. Without sincerity there would be nothing. Therefore the superior man values sincerity. Sincerity is not only the completion of one’s own self, it is that by which all things are completed. The completion of the self means humanity. The completion of all things means wisdom. (…)”[26]

So faithfulness to the ancient wisdom and sincerity are the guiding principles for a successful self-cultivation of a Junzi but of equal importance is to have the “right” friends: “take loyalty and trustworthiness as the pivot and have no friends who are not like yourself in this. If you err, do not be afraid to correct yourself.”[27], only this allows successful reflection.

A Junzi should be accompanied by people who are similar to him in order to serve as a master: “(…) If a person is apt in conduct and cautious in speech, stay near those who keep to the dao and corrects himself thereby, he may be said to love learning.”[28] Learning from others requires to have friends similar to oneself: “when walking in a group of three, my teachers are always present. I draw out what is good in them so as to emulate it myself, and what is not good in them so as to alter it in myself.”[29]

But not all friends are the right friends, so Confucius defines which type of friends are helpful: “(…) Friends who are straightforward, sincere, and have learned much improve you. Friends who are fawning, insincere, and crafty in speech diminish you.”[30] Straightforward and sincere friends are necessary for an open and constructive reflection on one’s own behavior: “My friends, do you believe I have secrets from you? I am without secrets. There is nothing I do that I do not share with you, my friends. That is who I am.”[31]

For finding the appropriate friend who can serve as master for one’s own self-cultivation the motivated student has to identify the people of humanity first. Confucius compares this with the sharpening of the necessary tools: “The Master said, The craftsman who wishes to do his work well must first sharpen his tools. When you dwell in a state, serve those of its grandees who are worthy men, befriend those of its gentlemen who are ren.”[32]

Reflection without the openness to alter one self’s behavior is useless in order to become a cultivated man. For a successful reflection someone has to make mistakes and has to be able to alter his behavior: “To err and not change – that, we may say, is to err.”[33] For a successful alteration, being self-critical is required on the way to cultivate someone’s self: “The Master said, the junzi seeks it in himself; the small man seeks it in others”[34] Moreover, the Junzi should be aware, that his knowledge is not complete: “to know when you know something, and to know when you don’t know, that’s knowledge.”[35]

For the attempt to reflect on oneself, “li” as behavioral propriety, already introduced in chapter 3.1, serves as guideline for a continuous and successful reflection: “conquer yourself and return to li: that is ren. If a person could conquer himself and return to li for a single day, the world would respond him with ren. Being ren proceeds from oneself, how could it come from others.” [36] The Junzi judges right and wrong according to li: “if it is not li, don’t look at it; if it is not li, don’t listen to it; if it is not li, don’t say it; if it is not li, don’t do it.”[37] In the context of self-reflection by observing, listening, saying and doing, the cultivated man decides by himself what is right according to “li”.

The Junzi, a selfless man of virtue

Through successful self-cultivation, “The Junzi is not a vessel”[38] and is therefore not limited in his capacity, he fits not only for designated uses – he is a universal talented man.

Confucius gives a clear guideline how selecting the appropriate leader for different positions. The leader in top level position is guided by perfected virtue and is able to lead each kind of department; for high level positions, the suitable leader is respected by the seniors and follows the way of righteousness; and finally the middle management position should be manned with persons who are trustworthy and follows the way of their boss. Book XIII chapter 2 of the Analects describes: “(…) The Master said, One who conducts himself with a sense of shame and who may be dispatched to the four quarters without disgracing his lord’s commission, such a one may be termed a gentleman. (…) next best when his clan calls him filial and his neighborhood district calls him respectful of elders. (…) next best Keeping to one’s word and following through in one’s actions – it has the ring of a petty man, but indeed, this would be next. (…)”[39]

But no matter in which position the Junzi is entrusted to lead people, the good leader does not seek the appreciation of others: “The Junzi is apprehensive that he may leave the world without his name remaining praised there.”[40] If he will be asked to serve as a teacher to lead people to the way of virtue in order to establish harmony he will take the responsibility and provide an exemplary character.

In this position, the Junzi regards his first duty in overcoming difficulties whereas the gain of success is regarded as a subsequent consideration: “people who are ren are first to shoulder difficulties and last to reap rewards. This may be called ren.”[41] Because he is free from personal favor, he exclusively serves the Way of Virtue: “The Junzi cherishes virtue, the small man cherishes land. The Junzi cherishes the examples men set, the small man cherishes the bounty they bestow.”[42] Also “The Master said: The junzi does not compete. Yet there is always archery, is there not? They mount the dais bowing and yielding, they descend and toast another. They compete at being junzis!”[43] Furthermore, “The Junzi is at ease without being arrogant; (…)”[44] and “(…) blames himself for lacking ability; he does not blame others for not recognizing him.”[45]

Because of his sincere character he has no problem to show his weaknesses, he allows himself to make mistakes which can be recognized by everyone: “The errors of a Junzi are like eclipses of the sun and moon: everyone sees them. Once he corrects them, everyone looks up to him.”[46] In order to show perfected virtue he should correct his errors in order to gain respect as an authentic person and serve as model for all others.

In his character, Confucian Junzi is not extravagant: “Extravagance leads towards disobedience; thrift leads towards uncouthness. Rather than be disobedient, it is better to be uncouth.”[47] He should be: “(…) Supportive, encouraging, congenial – such a man may be called a gentleman. Supportive and encouraging with his friends, congenial with his brothers.”[48]

“Zizhang asked about ren. The Master said, He who can enact five things in the world is ren. When asked for details he went on, Reverence, tolerance, trustworthiness, quickness, and generosity. He is reverent, hence he receives no insults; he is tolerant, hence he gains the multitudes; he is trustworthy, hence others entrust him with responsibilities; he is quick, hence he has accomplishments; he is generous, hence he is capable of being placed in charge of others.”[49]

Furthermore, for a man of virtue, “conscientiousness and altruism are not far from the Way”[50] so he can always act according the “Golden Rule”, as already introduced in chapter 3.1: “what I do not wish others to do to me, I do not wish to do to others”. The “Golden Rule” could be regarded as the most important rule which has to be followed by everyone and has special importance for the virtuous Junzi who serves as role model and teacher for all the others in treading the Way of virtue in order to establish harmony: “Zigong asked, It there a single saying that one may put in practice all one’s life? The Master said, That would be ‘reciprocity’: That which you do not desire, do not do to others.”[51]

In his behavior, “the Junzi is not beset with care or fear. (…) Surveying himself within and finding no fault, what care or fear could there be?”[52] If the man of virtues takes his duty in reflecting himself and after intensive reflection correcting his faults according to the Way of virtue, he can be sure in doing right and has no reason to be in fear.

The Junzi always acts according to the “Doctrine of the Mean” and therefore avoid the extremes: “The superior man exemplifies the Mean. The inferior man acts contrary to the Mean. The superior man exemplifies the Mean because, as a superior man, he can maintain the Mean at any time. The inferior man acts contrary to the Mean because, as an inferior man, he has no caution.”[53] Because “he never dares to go to the limit”[54] or showing extreme emotions he always keeps his neutral position: “The Junzi is inclusive and not a partisan”[55]

In his acting, the Junzi considers various opinions and dimensions and is never biased in his position: “The Junzi bears himself with dignity but does not contend; he joins with others, but does not become a partisan.”[56] Furthermore he is aware about his position, remains incorruptible and steadfast, and is acting simple and reticent: “(…) The Junzi acts in harmony with others but does not seek to be like them; (…)”, “(…) Incorruptibility, steadfastness, simplicity and reticence are near to ren”.[57] As a virtuous man, the Junzi “does what is proper to his position and does not want to go beyond this”[58]; like the North Star he keeps his position and all the people follow him to tread the Way of virtue.

Junzi, an exemplary man of righteousness

He who is appropriate for leading people is led by propriety and righteousness: “there is nothing he insists on, nothing he refuses, he simply aligns himself beside right.”[59]

In leading the people it is more important to live in accordance to humanity and righteousness than being an expert with professional expertise and know how to apply several tools: “Fan Chi asked to learn about farming grain. The Master said, better to ask an old peasant. He asked about raising vegetables. Better to ask an old gardener. (… )the Master said, …, if a ruler loved li, none among the people would dare be inattentive; if a ruler loved right, none would dare be unsubmissive; if a ruler loved trusthworthiness, none would dare be insincere. The people of the four quarters would come to him with their children strapped on their backs. Why ask about farming.”[60]

Through self-cultivation, the selfless Junzi is practicing humanity and teaches the people the way of righteousness: “The Junzi gives righteousness the topmost place. If a Junzi had valor but not righteousness, he would create chaos. (…)”[61] Therefore the righteous Junzi does not only recognize what it is right: “the Junzi comprehends according the right (…)”[62] it is important that he acts according to what is right: “to see the right and not do it is to lack courage”[63]. So he serves as role model for the people and becomes an accepted model of righteousness.

According to the Analects book XIV chapter 13, he speaks “but only when it was timely; in that way, people did not tire of his words. He laughed, but only when he was joyful; in that way, people did not tire of his laughter. He took things, but only when it was righteous; in that way, people did not tire of his taking.”[64] The Junzi is a man of deeds because before he speaks he is acting and afterwards he speaks according to his action: ”(…) his words correspond to his actions and his actions correspond to his words”[65]. In leading people, the Junzi is brilliant in his action, not in fine words: “(…) The Junzi is ashamed when his words outstrip his actions.”[66] He is cautious and therefore “slow of speech and quick in action.”[67]

Just through practicing filial piety the leader serves as loyal role model for his followers and teaches them how to behave toward the leader and within the organization in order to establish harmony: “When the Junzi is devoted to his parents, the people rise up as ren; when he does not discard his old comrades, the people are not dishonest.”[68] “(…) if you are filial and caring they will be loyal”[69]. “Therefore the superior man without going beyond his family, can bring education into completion in the whole state.”[70] The followers who are doing right will serve as models for the others who have to improve their qualities in practicing righteousness: “(…) if you raise up the good and instruct those who lack ability they will be persuaded.”[71]

The obedient follower

In his book of the same title, Mencius gives a clear separation between leading and led people: “Some labor with their minds and some labor with their strength. Those who labor with their minds govern others; those who labor with their strength are governed by others.”[72]

For this separation, the gain of wisdom through self-cultivation is the distinguishing criterion: “The Master said, There may be some who invent without prior knowledge.”[73] Those who are following the virtuous leader do not have to understand the Way of virtue: “The people can be made to follow it, they cannot be made to understand it.”[74]

The followers have to be loyal to their leader and follow him on the Way of Virtue in order to establish harmony. The obedient follower has to fulfill his assigned role which is modeled according to the defined relationships in superior and inferior positions as already presented within chapter 3.1[75] and has to obey the rules of propriety, defined by “li”. For example, in order to save his and his superior’s face, the follower should not argue against his superior: “In attending a ruler there are three mistakes. To speak of something before an appropriate time has come is to be impetuous; to fail to speak of something when an appropriate time has come is to be secretive; to speak without gauging the ruler’s expression is to be blind.”[76]

For obeying the rules of propriety successfully, the followers are expected to ask the leader as their teacher how to do things right: “Those who are not always saying, What shall I do? What shall I do? – I can do nothing with them.”[77]

Leading by teaching

In his role of teaching the followers, the Junzi is a role model of being ren and teaches them the way of righteousness through li: “The Master said: Guide them with policies and align them with punishments and the people will evade them and have no shame. Guide them with virtue and align them with li and the people will have a sense of shame and fulfill their roles.”[78] “Therefore the superior man must have the good qualities in himself before he may require them in other people.”[79]

In the Confucian idea of leadership, the perfected leader is successful in cultivating himself and teaches other people in order to help them to become cultivated and follow the Way of Virtue: “(…) if you raise up the good and instruct those who lack ability they will be persuaded.”[80] Not only the ability to perfect one’s own virtue makes a man a virtuous man but also the will and ability to help others to enlarge themselves is needed to become great: “Virtue is the root, while wealth is the branch.”[81] Only by treading the Way of virtue real harmony can be established within society. For this purpose the perfected leader has to follow the eight steps, described within The Great Learning:[82]

- Investigation of things

- Extend people’s knowledge

- Make their wills sincere

- Rectify their minds

- Cultivate their personal lives

- Regulate their families

- Bring order to the state

- Peace will be achieved

Investigate things

In his acting, the good leader “must not act on guesses, (one) must not demand absolute certainty, (one) must not be stubborn, (one) must not insist on oneself;”[83] therefore he first of all has to investigate the things accordingly: “The Junzi focuses his attention in nine ways. In observation, he focuses on clarity; in listening, he focuses on acuity; in facial expression, he focuses on gentleness; in bearing, he focuses on reverence; in words, he focuses on loyalty; in affairs, he focuses on attentiveness; in doubt he focuses on questioning; in anger, he focuses on troublesome consequences; in opportunities to gain, he focuses on right.”[84] With his advices Confucius has expressed the importance of investigation before making decisions; Investigation through listening to others and observing what is going on and what has to be done. The standard for making the decisions is the application of morality and righteousness. “If you listen to much, put aside what seems doubtful, and assert the remainder with care, your mistakes will be few. If you observe much, put aside what seems dangerous, and act upon the remainder with care, your regrets will be few. Few mistakes in speech, few regrets in action – a salary lies therein.”[85] So the duty of the leader is to investigate through listening and observation and making decisions by considering about what is good and bad according to the Confucian wisdom.

Extend their knowledge

The duty of the leader is to attract the right people in adequate number, ensure that they can make their living and finally teach and develop them according to the Way of Virtue: “The Master traveled to the state of Wei. (…) The Master said, How populous it is! (…) Enrich them. Once the people were enriched, (…). Teach them.”[86]

Confucius said: “To manage a state one needs li, (…)”[87] Because the followers do not have to comprehend the Way of Virtue, the virtuous leader teaches the follower the way of righteousness through “li”.

Li has an educational function for teaching the attitude and values which are incorporating “ren”: “The Junzi takes right as his basic substance; he puts it into practice with li, uses compliance to enact it and faithfulness to complete it.”[88] Therefore the leader as a teacher has to keep and teach the ancient wisdom recorded in the Classic Books. But he also has to acquire new knowledge continually according to the changing situation: “A person who can bring new warmth to the old while understanding the new is worth to take as a teacher.”[89]

The leader’s duty is to teach and instruct the people for developing them in order to get them ready to contribute to the common success:

“If a good man were to instruct the people for seven years, they would indeed be ready to go into battle.”[90] With his effort to develop his followers, the leader takes care about their welfare and life, like a father does for his own children: “not to teach the people how to fight in war may called discarding them.”[91]

Make their will sincere

As a superior man the Junzi seeks to help people to perfect their admirable qualities in order to cultivate their morally character: “The Junzi perfects what is beautiful in people, he does not perfect what is ugly.”[92] This can be gained by cherishing the followers and complementing their behavior: “(…) The Master said, Cherish people. When he asked about knowledge, the Master said, Know people, (…)The Master said, If you raise up the straight and place them over the crooked, the can make the crooked straight.”[93]

Through practicing ren the leader’s benevolence will lead the people to fulfill their duties and his loyalty instructs them. People do not have to be forced to act; they are motivated by the appreciation of the virtuous leader: “the Master said, If you cherish them can you not make them labor? If you are loyal to them, can you not instruct them?”[94]

Rectify their minds

Faith in the leader is one of the basic requirements which have to be given in order to make the followers fulfilling their obligations and doing their best to contribute for common objectives: “Zigong asked about governance. The Master said, Provide people with adequate food, provide them with adequate weapons, induce them to have faith in their ruler. Zigong said, If you had no choice but to dispense with one of those three things, which would it be? Dispense with weapon [the Master said]. If you had no choice but to dispense with one of those two things, which would it be? [Zigong asked. The Master answered] Dispense with food. From ancient times there has always been death. If the people do not have faith, the state cannot stand.”[95]

When the people trust their leader they will accept him as their great master who shows them the right way and the righteous followers serve as role model for the others: “Duke Ai asked, what should I do so that the people will obey? Confucius replied, raise up the straight and set them above the crooked and the people will obey (…).”[96] When the followers can trust their leader, they will do their best to perform in the appreciated way: “if he is upright in his person, he will perform without orders. If he is not upright in his person, though you give him orders, he will not carry them out.”[97] Only by performing in accord with the way of righteousness the followers could please their master: “The Junzi is easy to serve and hard to please. If you do not accord with the dao in pleasing him, he is not pleased (…)” [98] For this, the good leader: “(…) Provide[s] a leading example to (your) [his] officers. Pardon minor offences. Raise up the worthy. (…) Raise up those you recognize. (…)”[99]

Regulate their families

The teaching of filial piety is given the first priority in teaching righteousness: “It is rare to find a person who is filial to his parents and respectful of his elders, yet who likes to oppose his ruling superior. And never has there been one who does not like opposing his ruler who has raised a rebellion. The Junzi works on the root – one the root is plated, the dao is born. Filiality and respect for elders, are these not the roots of ren?”[100] By teaching filial piety the leader makes sure that the people respect his person like a son respect his father and the younger brother respect his elder brother.

Bring order to the state

Order to the state means order to society in which each individual has its fixed place linked to assigned responsibilities: “let the ruler be ruler, ministers ministers, fathers fathers, sons sons.”[101]

For this, the first required operation would be to rectify names: “(…) If the ruler of Wei were to entrust you with governance of his stage, what would be your first priority. The Master said, Most certainly, it would be to rectify names. (…) If names are not right then speech does not accord with things; if speech is not in accord with things, then affairs cannot be successful; when affairs are not successful, li (…) do not flourish; when li (…) do not flourish, then sanctions and punishments miss their mark, the people have no place to set their hands and fee. Therefore, when a Junzi gives things names, they may be properly spoken of, and what is said may be properly enacted. With regard to speech, the Junzi permits no carelessness.”[102]

But not only names must correspond to its actuality also the rank, duties and functions must be clearly defined and fully translated into action. Only then can a name be considered to be correct or rectified. Each person can behave according to the rituals and carry out righteousness to contribute harmony: “(…) Therefore men of wisdom sought to establish distinctions and instituted names to indicate actualities, on the one hand clearly to distinguish the noble and the humble and, on the other, to discriminate between similarities and differences. (…) [keeping this principle] there will be no danger of ideas being misunderstood and work encountering difficulties or being neglected.(…) Names have no correctness of their own. The correctness is given by convention. When the convention is established and the custom is formed, they are called correct names. (…)”[103]

The benefit of rectifying names is the effectiveness and efficiency of communication within the society. According to the Analects book VI chapter 21: “With men of middle level or higher, one may discuss the highest; with men below the middle rank, one may not discuss the highest.”[104] Furthermore is is described that “To fail to speak with someone whom it is worthwhile to speak with is to waste that person. To speak with someone whom it is not worthwhile to speak with is to waste words. The wise man wastes neither people nor words.”[105]

Because the leader loves his people he always will assign them with the suitable tasks and expect their performance according to their ability: “(…) when it comes to employing others, he only puts them to tasks they are fit to manage. (…)”[106]

For appropriate men in a state’s government, Confucius formulates strict and accurate moral requirements: “Zizhang asked Confucius, What must a man be like before he may participate in governance? Confucius said, If he honors the five beautiful things and casts out the four evil, then he may participate in governance. Zizhang said, What are the five beautiful things? The Master said, The Junzi is generous but not wasteful, a taskmaster of whom none complain, desirous but not greedy, dignified but not arrogant, awe-inspiring but not fearsome. Zizhang said, What do you mean by generous but not wasteful? The Master said, To reward people with that which benefits them, is that not to be generous but not wasteful? To pick a task that people can fulfill and set them to it, is that not to be a taskmaster of whom none complain? If one desires ren and obtains it, wherein is he greedy? If he never dares to be unmannerly, regardless of whether with many or a few, with the great or the small, is that not to be dignified but not arrogant? When the Junzi sets his cap and robes right, and makes his gaze reverent, such that people stare up at him in awe, is this not, indeed, to be awe-inspiring and not fearsome? Zizhang said, What are the four evils? The Master said, To execute people without having given them instruction is called cruelty; to inspect their work without warning is called oppressiveness; to demand timely completion while having been slow in giving orders is called thievery; to dole out stingily what must be given is called clerkishness.”[107]

Moreover he noted some non-acceptable characteristics for men occupying a leading position: “Zigong said, Does the Junzi have things he hates? The Master said, He does. He hates those who proclaim other men’s faults; he hates those who occupy inferior positions but who slander their superiors; he hates those who are valorous but lack li; he hates those who are bold but lack understanding. The Master went on, I hate those who think that having spied out things is wisdom; I hate those who think being uncompliant is valor; I hate those who think insulting others is straightforwardness.”[108]